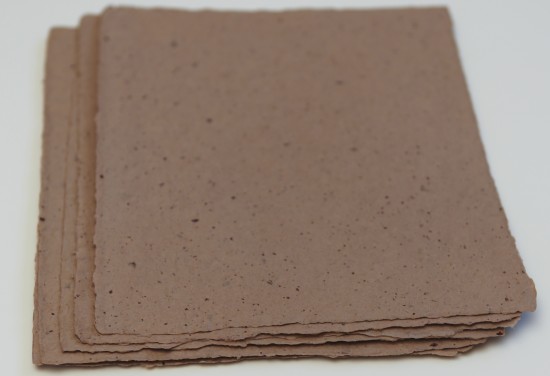

Jute paper from cacao sacks. The flecks are bits of cacao husks added when processing the paper pulp

Pam returning to the studio with a bike load of jute sacks. They are heavier than they look! |

Cacao beans are shipped in jute sacks. The sacks are not reusable to the chocolate maker but they can be repurposed into many things including paper. We are fortunate to have a bean-to-bar chocolate maker in our neighborhood and they provide us with a steady supply of sacks.

|

Left: the first step is to shake out all the cacao beans, remove the paper tags and twine, and cut out the seams. All these items can damage the beater.

Right: next step is to cut the sacks into small squares. Because cacao beans are fermented the sacks have a pungent odor. Alice at Dandelion thinks they smell like vinegar but I think they smell like feet.

|

The sacks are made of jute fiber and contain a lot of lignins. Lignins are organic compounds found in the cell walls of many plants. They provide strength to the plant but weaken paper and therefore must be removed.

Lignins dissolve in an alkaline solution and heat speeds up the process. Washing soda, soda ash, or lye are all acceptable choices. The fiber must simmer for 2-4 hours.

|

|

The fiber pot starts out with a Ph of 10-11. As the fiber cooks the alkaline consumes the lignins and by the end of the cycle the Ph is closer to neutral. The plant beds outside our studio are the perfect place to rinse fiber. The rinse water is not wasted and our plants appreciate the attention.

|

|

Left: the cooked fiber is put into a machine called a hollander beater. The beater has a paddle-wheel (called a roll) with a series of thin metal bars. Underneath the roll are more metal bars (called the bed plate). The roll and bed plate work together to beat the fiber into pulp.

Top right: a handful of cacao husks is added to the beater. This will add flecks to the finished paper and give it a more chocolaty look. The husks smell delicious!

Bottom right: the fiber beats down into pulp in about 20-30 minutes.

|

The final test is to put a bit of the pulp in a jar and add some water. Shaking the jar and holding it up to the light shows if there are any clumps or long fibers. The flecks you see are the bits of the cacao husk–the rest is the finely beaten jute.

At this point we can add sizing. Since we plan to use this paper for letterpress we are not going to size it. This is one advantage of being a papermaker–we can tailor the paper to specifically meet our needs.

|

The pulp is poured into a vat and water is added to create a thick slurry. The density of the slurry is what determines the thickness of the sheets. We are aiming for card stock so we’ll want a fairly dense slurry.

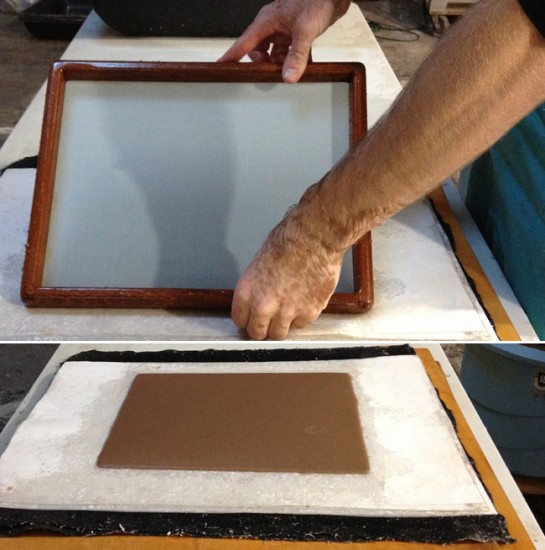

A mould and deckle is used to form the sheets. The mould and deckle is dipped into the vat at an angle and pulled straight up. A couple front-back/side-side shakes evenly settles the fibers as the water drains.

The deckle is removed and the mould is lined up so the new sheet will lie directly on top of the one below, separated by a piece of interfacing. Even pressure is put on the mould to get the sheet to release. The mould is peeled back leaving the newly formed sheet behind.

Top: the stack of formed sheets (called a post) is put in a hydraulic press to remove the excess water.

Pressed sheets are carefully placed into a drying box which consists of layers separated by a channeling system where the air can pass through (bottom right). The blower is set to pull air from the open side. The top is held down with weights so the paper can dry under pressure, creating perfectly flat sheets.

It takes about 8-10 hours for the paper to completely dry.

|

The final stage is to put the dried paper in a nipping press to cure.

|